USING COMMUNICATION TOOLS TO FOSTER CROSS-CULTURAL UNDERSTANDING

Gilbert Furstenberg

Massachusetts

Institute of Technology

Today when people are more and more likely to interact and work with members of other cultures, a new educational priority is fast emerging, namely the need for educators to provide students with the skills and knowledge that will enable them to communicate effectively across different cultures. Language teachers are in an excellent position to play a large role in this endeavor since they teach both language and culture. However, more often than not, culture is relegated to the background of language classes, while the development of linguistic competence occupies front stage. The main thrust of the project described here is to reverse this equation and make culture the core of a language class, focusing on the development of students’ in-depth understanding of a foreign culture. The Cultura project, started in 1997 at MIT [1] has been designed to develop cross-cultural understanding between French and American cultures, but since it is essentially a methodology it is applicable to the exploration of any two cultures, and versions in other languages have been developed elsewhere. [2] This paper will (1) set up the background and the context of Cultura; (2) define its goals and approach; (3) show how web-based resources and electronic communication tools connect and intersect in order to meet these objectives; (4) show how the use of these tools is bound to change the way culture is taught in the classroom.

The general focus throughout this article will be on the process that enables students to gradually and collaboratively construct and refine their understanding of the other culture both in and outside of class. Specific examples will be given of how students, with the help of their peers and the teacher, gradually develop into what Byram (1996) calls the “intercultural learner.”

CULTURA: ITS GOALS, TOOLS AND APPROACHGoals

There are many ways to define culture. The goal of Cultura is to develop understanding of what Hall (1959, 1966) calls “the silent language” and “the hidden dimension,” namely, concepts, attitudes, values, ways of interacting with and looking at the world (Furstenberg, 2001). Teaching these aspects of culture is a huge challenge: how can we teach something that is essentially elusive, inaccessible, and invisible? It is all the more difficult as our own culture tends to be very opaque to ourselves, which means that we are faced with a double invisibility, so to speak. The question is how to make what is doubly invisible more apparent. What we need is an approach and some tools.

Approach and Tools

Very simply, the tools are a combination of the World Wide Web and its related communication tools. The approach is a comparative, cross-cultural one, whereby American students who are taking an intermediate French class at MIT and French students who are taking an English class at a French university, or Grande Ecole, under the direction of our partner in France, work together during the larger part of a semester. Sharing a common calendar and a common website, students, at first individually and then collaboratively, analyze a variety of similar materials originating from both cultures that are presented in juxtaposition on the Web, and subsequently enter into cross-cultural dialogues about these materials via on-line discussion forums.

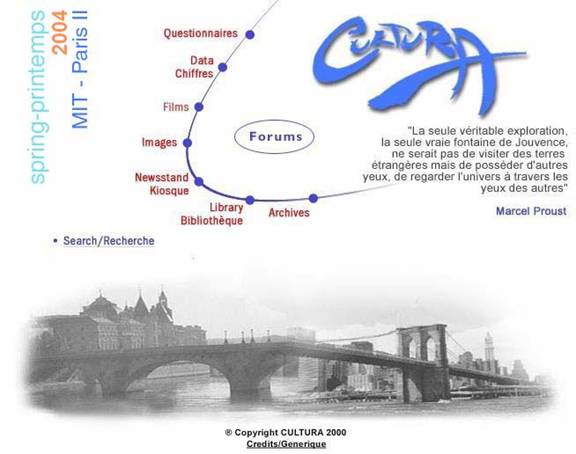

Figure 1 below shows the home page of the website (http://mit.edu/french/21f.303/spring2004) dedicated to Cultura. The website provides a virtual space where the Brooklyn Bridge in New York and the Pont Neuf in Paris connect and merge. The accompanying phrase by Marcel Proust (1923) fully epitomizes what the project strives for -- “The only true exploration, the only real fountain of youth would not be to visit foreign lands but to possess other eyes and look at the universe through the eyes of others” (pp. 257-259).

The curve in the shape of a C is visibly reminiscent of the first letter of Cultura, but it also represents an itinerary with several modules that represent stages on the students’ road to exploration and discovery.

Figure 1. Home page of the Cultura Project

|

|

Methodology

The overall methodology is a constructivist one whereby students, actively engaged in a process of discovery, constantly perceive and create new connections and gradually construct, with their peers and the help of the teacher, their own understanding of the subject matter (Brooks & Brooks, 1993).

Process

Within Cultura, the French and American students engage in the following activities:

1. They compare a variety of similar French and American materials that are presented in juxtaposition on the Web. These materials include answers to a series of questionnaires the American and French students fill out at the beginning of the semester and which they will subsequently analyze. The students’ field of investigation broadens as they compare national polls allowing them to put their findings into a much larger socio-cultural framework; discuss a French film and its American remake, adding a visual dimension to their explorations; and read French and American press, looking at the way the same international event is covered, for instance, in Le Monde and the New York Times. A new module has been added recently, allowing students to exchange images of their respective cultural realities around topics selected by them. Finally, the journey ends with students having access to a library of historical, literary, anthropological, and philosophical texts by French and American authors writing about each others’ cultures, as well as primary fundamental documents such as the Bill of Rights and the Déclaration des Droits de l’Homme, allowing them to have direct access to “expert” texts and to find validation of their own findings.

2. At the core of the project are on-line discussion forums that allow students to exchange in writing their viewpoints and perspectives on all the subjects at hand. Through these cross-cultural exchanges, written in their own native language, students share observations, send queries, and answer their counterparts’ questions with the goal of deepening their understanding of their transatlantic partners’ perspectives, in a continuous, reciprocal and collaborative process of construction of each other’s culture.

Questionnaires

Stage 1: Filling out the questionnaires

Understanding a foreign culture is a process, often a lifelong one. And like any process, journey or exploration, it needs to start somewhere. In the Cultura project, it starts with students anonymously answering a series of three questionnaires that are written in English and in French and are exact mirrors of each other. The MIT students respond in English, while the French students respond in French.

1. Word Association Questionnaire asks students to make associations with such words as school, police, money, elite, responsibility, individualism, freedom, work, success, power, and so forth.

2. Sentence Completion Questionnaire asks students to complete such sentences as “A good parent is someone who...”, “A good citizen is someone who …”, “A well-behaved child is someone who…”, “A good boss is someone who…”, “A good job…”, and so forth.

3. Hypothetical Situations Questionnaire asks students how they would react in such hypothetical situations, as “You are walking down the street in a big city. A stranger of the opposite sex approaches you with a big smile.” “You see a mother in a supermarket slap her child.” “You have been waiting in line for ten minutes and someone steps right in front of you.”

Stage 2: Analyzing the questionnaires

A few days later, student answers appear on the website, in a side-by-side format, allowing differences to immediately emerge and become visible. Below are some examples taken from different semesters.

The juxtaposition of the words banlieue/suburbs (each of which is the only possible translation of the other) clearly highlights how impossible it is to interchange the realities behind them. American and French students’ associations to these words are available at http://web.mit.edu/french/culturaNEH/spring2004_sample_site/answers/banlieue_w.htm. Whereas American students associate the word suburbs with words such as white, clean, houses, families, backyard, and white picket fence, the French associate banlieue with ghettos, chômage (“unemployment”), violence, and danger, a description much more often associated with an American inner city. Even though the words suburbs/banlieue cannot be translated in any other way, their representations cannot be transposed. The very process of juxtaposition allows their opposite underlying socio-economic realities to immediately emerge and become visible.

To support the claim that such cross-cultural encounters can indeed be powerful allies in the understanding of a foreign culture, a quote from the Russian philosopher Mikhail (1986) seems appropriate. He wrote, “A meaning only reveals its depths once it has encountered and come into contact with another foreign meaning” (pp. 6-7). This, we will see, applies to many other words, concepts, and situations.

In comparing and analyzing responses to the words individualism/individualisme, students discover much to their own dismay, that, even though the words are the same, the French and the Americans have radically different views of the concept. Whereas for the Americans, the connotations are in general extremely positive (free, freedom, independence, strength, pride), the French responses are replete with very negative words such as ego, egotism, egocentrism, indifference, and loneliness (http://web.mit.edu/french/culturaNEH/spring2004_sample_site/answers/individualisme_w.htm). A comparison of responses to what the French and MIT students consider to be a good parent reveals that for the French un bon parent is someone who educates in the French sense of the word, i.e., who guides, helps, and instills values, whereas a good parent for Americans is someone who is loving and caring (http://web.mit.edu/french/culturaNEH/spring2004_sample_site/archives/2001f/answers/bonparent.htm).

A detailed analysis of French and American responses to a situation at the bank, where “An employee reads your name on the check and addresses you with your first name” reveals to the students a wealth of cultural information and insights. The French answers, as opposed to the American ones, highlight the high value the French place on respect for social norms and conventions, when dealing with strangers in a professional context. Whereas, there are responses on both sides indicating that this would not pose a problem, the number of French students who react negatively to first name use is much higher. Their reactions range from mild disapproval such as “It’s a little bit too familiar, a little too friendly” to a more assertive stance, often tinged with a touch of irony or sarcasm, where they feel the violator of social norms needs to taught a lesson, “I would ask him whether we know each other,” “I would tell [emphasis mine] him we don’t know each other” or “We did not raise pigs together.” Some French students even express outrage. Students wrote “He owes me respect and has to call me by my family name”, “His position does not authorize him to do such a thing.” All of these examples make it abundantly clear to the American students that in France one does not/must not interact on a first name basis if one does not know someone personally, highlighting along the way the significance of social hierarchy and giving a very clear signal that there are strict boundaries that are not to be crossed (http://web.mit.edu/french/culturaNEH/spring2004_sample_site/archives/2004s/answers/bank_r.html).

It is very important to emphasize, from a methodological point of view, that these observations are made by the students on their own, as they analyze the responses very much in the same way as cultural anthropologists analyze raw data. They are the ones to discover in a very concrete way the high value the French place on formality, as opposed to teachers telling them about it in the abstract and in a cultural vacuum. This constructivist approach is radically different from the traditional learning environment in which the teacher is the one telling students how the French view the notion of individualism. It is also important to note that students do not necessarily see everything. They often take a perfunctory look and miss very important points. And this is where the teacher has the crucial task of providing students with guidelines on how to compare documents, such as counting the number of occurrences of the same word, creating categories, looking for cross-language equivalents, and noticing responses that appear on one side only.

These discoveries, of course, will lead to very interesting conversations in the forums about issues of formality, hierarchy, of the public vs. the private sphere, of where and how one draws the line between formality and informality, and the circumstances surrounding the use of tu vs. vous.

Stage 3: Making connections among answers to the questionnaires

Students share their discoveries in the classroom. They are encouraged to make connections among the questionnaires and to uncover patterns across them. Working in groups, students exchange their individual observations with each other, and then summarize their findings on white boards. For an illustration of this process, click on http://web.mit.edu/french/culturaNEH/classroom/pages/class14.htm) and http://web.mit.edu/french/culturaNEH/classroom/pages/class12.htm.

White boards play a vital role by making the observations visible to the whole class and allowing students to look across several sentences. Students then go from board to board, looking for commonalities in the responses (http://web.mit.edu/french/culturaNEH/classroom/pages/class19.htm). They draw arrows on the board, literally connecting different phrases (http://web.mit.edu/french/culturaNEH/classroom/pages/u18.htm) to see patterns emerge (http://web.mit.edu/french/culturaNEH/classroom/pages/class11.htm).

For instance, in the process of looking across responses to several questionnaires that asked for definitions of a good parent, a good doctor, or a good teacher, students discover that Americans tend to inject an affective slant into the relationships, whereas the French tend to look at them from a much more rational or distant point of view. Students noticed that the French tended to give responses pertaining to the role or function of that person. Un bon médecin and un bon prof are, above all, professionally competent, and a French good parent is someone who instills values in his/her children. Americans, on the other hand, seem to place a higher value on affective qualities. For them, a good parent loves unconditionally, a good doctor is caring, a good teacher is someone who can teach and [emphasis mine] care, who cares about his/her students, who deeply cares about the learning process, expressions that are actually very difficult to translate into French.

By analyzing and contrasting French and American attitudes towards work and school, for instance, students discover that Americans tend to put more emphasis on tangible rewards, results and achievements. For them, a good student is someone who gets good grades; a good job is one that pays well and gives promotions. French students, on the other hand, focus more on non-tangible rewards such as épanouissement “personal fulfillment”.

Like cultural archaeologists, students bring patterns to light and make initial connections that they will later attempt to confirm or revise in the light of new materials they will analyze.

Forums

Forums occupy a central position on the Cultura Web site symbolizing how crucial they are in this cultural exploration (http://mit.edu/french/21f.303/spring2004). This is where students ask their counterparts for help in deciphering the meanings of some words or concepts, where they present their own hypotheses and points of view, ask for help in verifying their assumptions and hypotheses, raise issues, and respond to their partners’ queries.

As we designed Cultura, we made three important decisions concerning the forums: (1) they would be written in the students’ native language, (2) they would be asynchronous, and (3) the teachers should never interfere. The fact that students write in L1 is a frequently misunderstood aspect of Cultura but it was a deliberate, carefully thought-out decision that seemed to us the only appropriate way to truly reach our stated objectives, i.e., the development of in-depth understanding of the other culture. Its benefits are threefold: (1) it puts all students on an equal linguistic footing; (2) students, not being bound by limited linguistic abilities, can express their views fully and in detail, formulate questions and hypotheses clearly, and provide complex, nuanced information; (3) student-generated texts provide the foreign partners with rich sources of authentic reading, and, in turn, become new objects of linguistic and cultural analysis, highlighting the different ways in which cultures can be expressed. It is also important to note that these postings are done outside of class and do not take anything away from students, contact time with the L2. On the contrary, the richness of language and ideas coming from L2 partners more than offsets what can be first perceived as a disadvantage.

It also seemed to us that asynchronous forums would better serve our purposes as they allow for more deliberate and thoughtful reflection on the part of the students. Finally, we felt it was important that forums be led entirely by the students who would be free to take them in any direction. As teachers, we did not want to be seen as interfering or even acting as mediators. The direct link between the students was very important to us.

Sample forum entries

Each word, sentence, or situation offered for analysis led to a forum that provided yet another crucial resource for helping students read between the cultural lines.

The forum about the bank employee calling the client by the first name elicited a high level interest on the part of the MIT students (some of them of Asian origin) who shared their personal experiences about formality vs. informality, and who were very curious to know why the French students so strongly disapproved of the bank teller addressing them by their first name. A full transcript of this forum can be seen at http://web.mit.edu/french/culturaNEH/spring2004_sample_site/archives/2004s/forums/bank_r.html. Below are some sample entries.

Here is what Susanna (an Asian student) wrote:

"I come from an Asian background. It was not until two years ago, I went to an international high school in U.K. and started calling my teachers and housemasters by their first name. I was very used to addressing people (especially my teachers and other strangers) by their titles to show my respect for them. I was shocked when I first realized that it was alright not to address those people by 'Mr.', 'Dr.', 'Ms.'... which, however, I gradually got used to after a couple of weeks. I am speculating that this might be one of the reason [sic] why some students from France would respond to the situation by finding it uneasy to be addressed by their first name at the bank teller. Would this be a correct speculation?"

Talking about formality vs. informality, Alicia, another MIT student, then shared her own experience and asked a series of very pointed questions:

"It seems that there is a much higher level of formality in France than there is in America when it comes to interactions with people we don't know. I think, in general, America has pretty informal traditions when it comes to addressing people. For example, my employer asks me to call him by his first name. Also, many people will address their step-parents by first name instead of calling them "Mom" or "Dad." So, for me, it isn't strange for others to address me by my first name. I was wondering, what kinds of formalities exist in France? Do you automatically address people by their family name? For example, if you go over to your friend's house, do you address their parents by first name or by last name? (In America, a lot of people would address friends' parents by first names)."

Below are some other questions posed by MIT students:

"When is it that you transition from being called by your first name to being called by your last name? Is there a marked moment? Also, is there a time when people transition from addressing you with "tutoier" [sic] to 'vousvoyer' [sic]?"

"When is it okay to call someone by their first name and use "tu"? For how long do you have to know them?"

"Does age matter? When people have the same age it is fine to address each other using first name? Is that correct?"

Here is how a French student tries to clarify things. The following is a translation from the French:

"Alicia is right. In France we are rather formal when we talk to people we do not know. [...] we call our teachers Monsieur or Madame. This phenomenon actually exists since kindergarten when we address our teachers with “Maître” or “Maîtresse”. As far as our parents’ friends, if we have never met them it is true that the “vous” form is necessary. I think the transition from the “vouvoiement” to the “tutoiement” takes place when the person is no longer unknown to us, that the age difference is not too high and that the function does not impose a particular form of respect."

Besides making the MIT students aware of the complex interplay between tu and vous and of the number of conditions that need to be met until one can start using the tu form, such remarks make that issue concrete and real for them.

The conversations in the forums bring rich and complex information, providing students with a valuable insider’s view that sheds welcome light on issues, such as the form of address, that often remain quite opaque. It is during these conversations that the students’ diverse ethnic backgrounds and experiences often emerge, providing yet another voice.

Cultural Modules

So far, students have been working solely with answers to the three initial questionnaires provided by their transatlantic partners. Even though they learned a lot from their partners, we felt it was important to broaden their horizons and give them access to a range of other materials

National opinion polls

The next module, entitled Data/Chiffres, allows students to place the observations they have made up to this point within a national socio-cultural framework by giving them access to several American and French polling institutes (http://web.mit.edu/french/21f.303/spring2004/index_data.htm). Students are asked to explore statistics and opinion polls that will either confirm or contradict their earlier observations.

In their search, students might come across a poll that questioned the French about their notion of happiness (http://www.tns-sofres.com/etudes/pol/281004_bonheur_r.htm). In reading the answers to the question “Among the following items, which contribute most to your happiness?” students might observe that what counts most to the French is their family (52% put it first), while their professional life plays a much smaller role (only 21% believe that a fulfilling professional life contributes to their happiness). This particular poll might reinforce an observation American students had made in the analysis of the answers to the questionnaires, that family is extremely important to the French, whereas work is much less so. Looking at such polls is important because it validates the students’ own findings. This is further reinforced by forum discussions in which students querying each other about the importance of work in their lives. Contradictions between the national opinion polls and the answers to the questionnaires generates even more interesting questions and discussions, with students trying to figure out what is real and what is not.

Film

This module allows students to compare French films and their American remakes. It provides yet another entry into the world of cultural differences by adding a key visual dimension. We have worked for a very long time with the 1985 French film Trois Hommes et un Couffin and its 1987 American remake Three Men and a Baby. Students on both sides of the Atlantic watch the movies during the same week, after which they embark upon on-line discussions. The following example illustrates how students attempt to put together the cultural jigsaw puzzle by looking for confirmation and contradictions.

Both the French and the American students noticed that the police were treated very differently in the two films. In the French movie, the police are made fun of, and the main characters choose to assist the drug traffickers rather than the police, even helping them to escape. In the American movie, the very opposite happens with the characters helping the police capture the drug traffickers.

The comments below illustrate how both sets of students attempt to explain the reasons for the difference. The forum discussion can be viewed at http://mit.edu/french/culturaNEH/cultura2001/archives/int/forums/menandpolice.html.

Stéphane (comment 1) and Sebastien (comment 4) are wondering whether the French reaction has anything to do with the perceived and even legendary aversion of the French toward authority. To which, Allison (comment 4.1) reacts by writing:

"Hi Sebastien. I am surprised to hear that you think that the French don't accept authority well, and that is why you think the men didn't cooperate in the French movie. In the word associations for "police" and "authority", the French responses were much more positive than the American. Also, I was looking at the opinion polls on the Cultura page, and one poll asked French people if they had faith in the police... 70% said yes. There seems to be a contradiction here... What are your thoughts on this?" [emphasis mine]

Fabrice, a French student, attempts to explain it in comment 13, given in translation below:

"BonjourThe contradiction that shows that 70% of the French trust their national police and the fact that in the film, the police are circumvented is characteristic of the fact that the French always do the opposite of what they say in public. We fear authority, so we say we trust it. But behind its back, we don’t think twice about it or worse we try to go around it."

This last remark by Fabrice, of course, throws yet another wrench into the equation, as it implicitly warns American students that they might need to read between the cultural lines.

Library

The Library/Bibliothèque module (http://web.mit.edu/french/culturaNEH/spring2004_sample_site/index_libr.htm) contains a variety of historical, literary, philosophical, and anthropological excerpts from primary and secondary texts by American authors about France, e.g., Edith Wharton and Polly Platt, or by French authors writing about the U.S., e.g., Simone de Beauvoir and Jean Baudrillard. This helps bring a multiplicity of intersecting perspectives on both cultures.

Reading such excerpts at the end rather than at the beginning of their cultural journey, takes on a lot more significance for the students. These texts help them assess how far they have come along in the process of deciphering French culture. As a matter of fact, students are often surprised to discover in these texts points of view and insights that they themselves had developed, to the point where their perceptions, unbeknownst to them, match the findings of cross-cultural experts.

They may, for instance, come across an excerpt from de Tocqueville (1961) (http://web.mit.edu/french/21f.303/spring2004/index_libr.htm):

The great advantage of Americans is to have reached democracy without having to suffer democratic revolutions and to have been born equal instead of becoming equal [emphasis mine]” (p. 147).

These words are an eerie echo of an earlier comment by Matthew, an MIT student, in the forum on individualism:

"The United States grew out of a desire to be independent from Britain where as [sic] France grew out of a desire for equality for all. The French revolution resulted in the removal of nobles with an unequal share of rights and privileges. Americans view individualism as growing above your environment to be the most you can."

What extraordinary validation for this student! Unbeknownst to him, he had put his finger on the reasons why the French place so much emphasis on equal rights, as opposed to individual rights. This type of insight, if not commonplace, is not unusual either. It illustrates how deep and insightful some of the students’ comments are and how proficient they had become at identifying cultural features and making relevant connections, to the point where their perceptions match those of cross-cultural experts.

These historical and literary texts also serve to bring out the historical and philosophical roots of the cultural phenomena the students themselves have discovered. For instance when comparing the American Bill of Rights and the French Déclaration des Droits de l’Homme, American students discover the all-important Article 4 in the latter that reads:

Freedom consists of being able to do everything that is not harmful to others: consequently, the only limits to the exercise of each man’s natural rights are those that guarantee the other members of society the enjoyment of the same rights.

This single phrase suddenly illuminates for the Americans the roots of French attitudes toward the notion that freedom is limited – a view that American students had first discovered at the beginning of the semester when they analyzed responses to the words freedom/liberté.

The reading of Déclaration des Droits de l’Homme often brings the discussion back to the earlier topic of freedom, but this time seen through a different lens. After reading it, Kamal, an MIT student, wrote:

"It seems that the French have a different idea of liberty than most Americans. In article 4 of the French bill of rights it says that liberty is being able to do all that does not harm others. This is different from America where we are given certain rights whether or not they affect others (free speech, freedom of the press, right to bear arms, freedom of association).

This reminds me of when the French government sued yahoo.com for offering Nazi memorabilia on its auctions website. In France I guess it is illegal to sell anything having to do with the Nazis. This law seems ridiculous to most Americans. What are your opinions on those types of laws and that case in particular?"

This provoked the following response from R.H., a French student:

"In response to Kamal’s message, I think it is normal [emphasis mine] for the Government to want to forbid the sale or purchase of Nazi objects. They fuel an anti-democratic ideology that flaunts inequality. I am surprised that the concept of freedom in the U.S. is defined as inalienable rights (freedom of the press and speech) since in the case of Yahoo, this encourages Nazi groups to express themselves publicly even though they are by definition opposed to citizens’ rights. I am not saying that this will bring about the installation of a Nazi (or pro-Nazi) government in a country that is too permissive, but if a group of people proclaims themselves to be against citizens’ rights [...] then it seems normal [emphasis mine] to me to prevent them from publicly spreading that kind of ideology."

This response clearly illustrates yet another aspect of the French culture, namely, the importance to set limits that cannot to be transgressed, whether it has to do with raising a child, with saying tu at inappropriate times, or with Government policies.

Photo projects

In the last two semesters, we added a feature that enables students to exchange not only opinions through written on-line forums, but also visual representations of their respective worlds, thus making the cultural reality they live in even more truly visible to their transatlantic peers. Not only do the students’ photos add a very concrete and essential dimension, but they themselves also become, like the forums, objects of analysis and form the basis for new discoveries and insights by providing yet another opportunity for making additional connections.

Students on each side of the Atlantic decide together which topics they want to illustrate, then upload their images to the Cultura website. [1] Each image becomes the topic for subsequent on-line discussions. Thus far, a variety of topics have been illustrated, including a French banlieue and an American suburb, the subway in Boston and Métro in Paris, an American party and a French fête.

Below is an example of an exchange about the photos. One of the topics selected by students in the Spring of 2004 was the daily life of a student at MIT and one at the University of Paris II. One MIT student posted a picture of a food truck and in the accompanying message explained that it is a very popular option because the food is quite good and cheaper than anywhere else on campus. Caroline, a French student, reacted in this way. Below is a translation of her response:

"Strange! It would never occur to me to buy food from a food truck because the hygiene cannot be very good!! (putting on its head the commonly held notion that the French do not care about hygiene) […] Personally, I much prefer to buy a sandwich or a salad at a good bakery (see photo of our meals)."

At which point, Gaëtane, another French student, sent a picture of an array of very appetizing food at the “bon boulanger du coin” (corner bakery), explaining in great detail what she usually eats for lunch, along with how much it costs. Below is a translation of her response:

"Alas, we cannot go home for lunch (revealing her desire do so if she could), so we go to a little bakery near the IUP (Institut Universitaire Professionnel within Paris II where they study). There are a lot of choices, as you can see: many sandwiches, quiches with bacon and leeks, slices of pizza. Often we take the 5-euro option that includes a sandwich, a small coke or an Orangina, a dessert which can be apple sauce or a small viennoiserie (pain brioche with chocolate). That’s it. What about you? What do you eat for lunch???"

When comparing the photos documenting their daily lives taken by MIT and those taken by French students, Americans noticed, for instance, that the French tended to take and post more official photos of their class as a group, and more exterior photos showing the outside of things as opposed to the Americans who showed the inside of a dorm room and individuals in very personal poses such as sleeping. Americans related this observation to the tendency by the French, which they had noticed earlier, to keep a certain distance between their public and private lives. They also related this to another observation they had made earlier about the avoidance of the first person personal pronouns je and moi by the French.

It was evident that the American students reflected on the images the French were projecting about themselves and not simply on the content of these images, revealing their capacity to look beyond the surface, to make connections and to see the larger picture, thus becoming what Michael Byram (1997) defines as a true intercultural speaker with the term speaker being taken here in the broader sense of the word:

The intercultural speaker can “read” a document or event, analyzing its origins/sources — e.g., in the media, in political speech or historical writing — and the meanings and values which arise from a national or other ethnocentric perspective (stereotypes, historical connotations in texts) and which are presupposed and implicit, leading to conclusions which can be challenged from a different perspective. […] The intercultural speaker can identify causes of misunderstanding (e.g., use of concepts apparently similar but with different meanings or connotations) [...] The intercultural speaker can use their explanations of sources of misunderstanding and dysfunction to help interlocutors overcome conflicting perspectives; can explain the perspective of each and the origins of those perspectives in terms accessible to the other” (p. 61).

CONCLUSION

It is now obvious that the use of electronic media generates a new pedagogy that totally changes the roles of student and teacher. Students now take center stage and are involved in the very process of learning by exploring, analyzing and constructing, individually as well as collaboratively, their understanding of the foreign culture. They themselves research, question and revisit issues, make connections, and note contradictions, constantly expanding and refining their knowledge and understanding in the light of new materials.

This constitutes a major shift in educational practice. As teachers, we often want to make sure that students understand what we want them to understand, see what we want them to see, and learn what we want them to learn. We want to be in control of the end result. A constructivist approach, such as Cultura, reverses this notion by not expecting students to tell us what we want them to know, but to tell us what they have found, seen, observed and learned. But for that to happen, we need to make the process transparent. We also need to design appropriate interactive and collaborative classroom activities, as well as evaluation tools that focus on the process, such as log books and papers where students are asked to record their observations and regularly synthesize their findings, making sure along the way that they probe deeper and present more cogent arguments.

What interactive technologies do best is to focus the students’ attention on the process of learning, of acquiring knowledge and of building that knowledge. We believe that process to be central. Let us make sure that in the classroom our students do observe, analyze, create links, raise questions, develop new insights, arrive at new interpretations, synthesize and constantly refine their understanding of complex matters in a cooperative pursuit of knowledge. If that happens, the classroom will then become a place where teachers and learners work side by side, a place where teaching and learning truly come together, for the benefit of both. This new reality is made possible by technology, certainly. But it is also the result of the ways in which technology can expand and give new meaning to what it means to teach.

NOTES

[1]The initial Cultura Project was first started in 1997 thanks to a grant from the Consortium for Foreign Language Teaching and Learning based at Yale University, and then by a subsequent three-year grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities. It was developed by Sabine Levet (now at Brandeis), Shoggy Waryn (who now teaches at Brown), and myself. Cultura has allowed us to amass a large corpus of data and create archives that are accessible to everyone at http://web.mit.edu/french/culturaNEH/spring2004_sample_site/index_arch.htm

Other French Cultura projects have been developed or are being developed at Smith College and the University of Chicago.

[2] Versions of Cultura have also been developed in German at the University of California at Berkeley and at Santa Barbara, in Italian at the University of Pennsylvania, in Russian and Spanish at Brown University and Barnard University. A Japanese version is in the process of being developed at the University of Washington.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Gilberte Furstenberg is a Senior Lecturer in French at MIT. She was born in France and educated in France at the Faculté des Lettres of Lille where she received her Agrégation. She is the main author of two award-winning multimedia programs: A la Rencontre de Philippe and Dans un Quartier de Paris. She has been teaching French language and culture courses at MIT for the last 25 years.

REFERENCES

Bakhtin, M. (1986). Response to a question from the Novy Mir editorial staff. In M. Bakhtin, Speech genres & other late essays. Austin, Texas: University of Texas Press.

Brooks, J. & Brooks, M. (1999). In search of understanding: The case for constructivist classrooms. The Association for Supervision & Curriculum Development.

Byram, M. (1997). Teaching and assessing intercultural communicative competence. Clevedon, England: Multilingual Matters.

De Tocqueville, A. (1961). De la Démocratie en Amérique. Paris: Gallimard.

Furstenberg, G., Levet, S., English, K., & Maillet, K. (2001). Giving a voice to the silent language of culture: The Cultura Project. Language Learning & Technology, 5(1), 55-102. Retrieved September 15, 2005 from http://llt.msu.edu/vol5num1/furstenberg/default.html.

Hall, E. (1959). The silent language. Garden City, NY: Doubleday.

Hall, E. (1966). The hidden dimension. Garden City, NY: Doubleday.

Proust, M. (1923). La prisonnière. Paris: Gallimard,

Contact: Editors

Copyright © 2005 National Foreign Language Resource Center

Articles are copyrighted by their respective authors.