A HYBRID BUSINESS GERMAN COURSE[1]

Annette Kym

Hunter College, City University of New York

ABSTRACT

This article describes the planning and teaching phase of a hybrid Business German course, and examines the results of a survey conducted over a period of four semesters. The first part of the article focuses on the integration of the face-to-face and on-line components, and the design of task-based activities related to the topics introduced in the textbook. Special attention is given to the development of concrete tasks that are geared to the actual proficiency levels of the students, and to projects that develop cross-cultural competency through on-line discussions with contacts in Germany and in multinational companies in the U.S. The second part of the paper discusses the results of a student survey and their implications for designing hybrid courses.

PART I: PLANNING AND TEACHING PHASE

Background

In the late 1990s, many institutions invested heavily in e-learning or in integrating technology into teaching. The City University of New York, of which Hunter College is a part, received a large grant for faculty development from the Alfred E. Sloan Foundation. The goal was to prepare a cadre of faculty in different disciplines to design and teach on-line and hybrid courses in which part of the material would be taught on-line. Hunter had just acquired a site license for BlackBoard ( http://coursesites.blackboard.com/), a widely used course management software program, and was eager for the faculty to use this course-delivery platform. I had considerable previous experience in offering distance-learning classes in German over interactive television between Hunter College and Brooklyn College and was happy to seize this new opportunity. The BlackBoard site was rather generic, and the faculty training offered at the central CUNY computing facility consisted primarily of familiarization with the interface. However, successful on-line learning does not consist of merely putting lecture notes on BlackBoard, posting links, or adding PowerPoint slides to a lecture. New pedagogies and different approaches to managing on-line courses have to be developed. This must be driven by pedagogy and not by technology, but as Hara and Kling (1999) state, “High quality online education is neither cheap nor easy” (pp.17-18). Zemsky & Massy (2004) give a number of reasons why on-line courses are not always successful. Among them are lack of faculty prepared to thoroughly reassess the way they teach with technology, and the lack of investment of time and finances on the part of faculty and institutions.

For the courses I intended to offer, I needed discipline-specific training focusing on pedagogy, rather than technology, in order to adapt a traditional foreign language course to a hybrid environment. In the summer of 2001, I attended a two-week Summer Institute organized by the National Foreign Language Resource Center at the University of Hawai‘i at Manoa entitled “Developing Web-based Foreign Language Learning Environments.” Since the number of participants at the Summer Institute was small, individual guidance on pedagogical as well as technical issues was provided.

Rationale for a Hybrid Format

The first selection for this new delivery method was a two-course sequence in Business German (German 312 and 313), which I had taught previously in a traditional format. Since the students were not in remote locations and the class was not intended for learners outside the CUNY system, the hybrid format, with half of the classes offered on-line and half in a traditional face-to-face environment, seemed appropriate. This format made it possible to work with all modalities, including speaking. Another, mostly practical, reason for using this arrangement was the late evening meeting time of the class. The course content also lent itself to this format because in today’s business world communication flows electronically, and simulating this flow in a class setting gave the students practical experience on a technological as well as on a linguistic level. Electronic communication transcends geographic borders and allows for exchanges with transatlantic partners and business executives working for multinational firms. The on-line environment makes it possible to establish direct links to the target culture. All on-line discussions could be carried out asynchronously. Students, instructor, and guests could post their contributions and follow-up questions in the Discussion Board forum on the BlackBoard site.

Course Objectives

The objectives of the two-semester sequence were to develop the students’ German language and the cultural proficiency necessary to work in an entry-level position requiring knowledge of German. Since Hunter College does not offer a major in Business Administration, many students were German majors who wanted to broaden their language skills in areas pertaining to business and economics. Therefore, the courses were not designed to teach business and economics per se, but to introduce students to general concepts which would serve as a foundation for developing more sophisticated language skills. The development of cross-cultural competencies was also one of the primary objectives.

Prerequisites

The prerequisite for German 312 is one conversation and composition course beyond the four-semester language requirement. German 312 is a prerequisite for German 313. Neither course is open to native speakers of German. Since Hunter has a large ethnically diverse transfer and non-traditional student population, learners with other backgrounds who can demonstrate the necessary linguistic proficiency can also be admitted with the permission of the instructor. Students could take one or both courses, and credit was granted for each course individually.

Enrollments and Student Profiles

Enrollment statistics for the four courses discussed in this article are presented in Table 1 below.

Table 1. Enrollment Statistics

| German 312 |

German 313 |

|

|

18 |

|

|

9 |

|

|

13 |

|

|

13 |

All learners lived in the New York City metropolitan area, but originated from 19 different countries. Such diversity is quite the norm at Hunter College. Taking such an international student body into account, the German Department at Hunter has developed over the years a well-articulated curriculum to accommodate our own students progressing through the normal course sequence as well as those who started their language studies elsewhere. Oral Proficiency Interviews and writing assessments based on the ACTFL Proficiency Guidelines-Speaking (http://www.actfl.org/i4a/pages/index.cfm?pageid=3325), 1999 and ACTFL Preliminary Proficiency Guidelines-Writing, 2001 (http://www.actfl.org/i4a/pages/index.cfm?pageid=3326) are given on a regular basis every semester. Based on these assessments, individual short-term and long-term learning goals are developed. A sample writing assessment can be found in Appendix A.

Student proficiency in speaking and writing ranged from Intermediate Mid to Superior on the ACTFL Scale, with the majority clustering around the Intermediate High/Advanced Low levels. The implications of such variation in linguistic skills for the planning of the courses will be discussed below.

Challenges and Solutions

There is general agreement that the preparation of on-line courses, particularly in the initial phase, requires a greater investment of time than preparation for regular courses. A hybrid course that combines the advantages of a traditional face-to-face setting with an on-line environment may seem easier to plan since some of the difficulties associated with web-based learning, such as lack of physical contact, absence of non-verbal communication, and total dependence on technology, do not play a major role. On the other hand, the coordination of the two elements poses other challenges for the instructor. Neither one should be carried out as a separate strand nor should the on-line component merely be viewed as a vehicle for homework assignments. The two must be interwoven, each carrying the discussion forward. In my case, the textbook German for Business and Economics (Paulsell, Gramberg & Evans, 2000) provided the general thread linking the two components. The book is accompanied by a multimedia CD-ROM containing listening texts and contextualized exercises. Having this tool and hosting the course on the ready-made BlackBoard platform allowed me to focus my energies on pedagogical and instructional design issues, namely logical design of the web page and adaptation of tasks and materials. This was important because on-line courses fail all too readily if the traditional lecture format is simply transferred to a course management system without adaptation of the lessons to a different learning environment (Brandl, 2002; Hara & Kling, 1999; Zempsky & Massey, 2004).

Design of the Course Pages

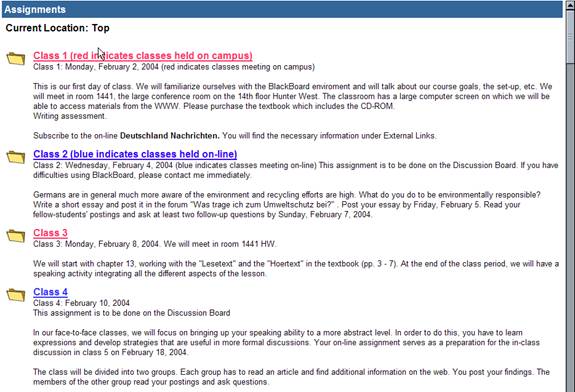

The course was offered for the first time in a hybrid format in 2001 using BlackBoard. This course delivery platform has limited flexibility for individual adaptation. In my initial design, I organized the assignments in folders according to the chapters in the textbook, with individual assignments numbered in each folder. The Discussion Board was ordered chronologically by chapter and assignment.

Even though I had given much thought to this design and it looked appealing, it proved confusing to the students, and required too much navigation and waiting for web pages to load. Students were very vocal about this in their first evaluation of the course, and in subsequent semesters I changed the design so that assignments were simply listed by class number and date, as can be seen in Figure 1. This reorganization eliminated confusion and contributed to greater ease of navigation.

Figure 1. Sample Web Page with Assignments.

Activities

Omaggio Hadley defines task-based activities as “activities that involve the completion of real-world tasks” (p. 104). Designing appropriate and engaging tasks is a challenge, particularly since it has to take place in advance of the course when the make-up of the class and the proficiency levels of the participants are not yet known. I prepared the course with a range of learners at the ACTFL Intermediate High to Advanced High levels in mind, but fine-tuning was possible only when the actual class started. In a face-to-face environment, it is possible to quickly adjust to the proficiency level of the students; however, in an on-line environment adjusting proves to be more difficult. As it turned out, in two of the four classes, the levels ranged from Intermediate Mid to Superior. The students at the lower end of the scale were able to carry out uncomplicated communicative tasks on concrete topics and could meet practical writing needs, e.g., compose simple messages, letters, requests for information, and ask and answer questions, whereas the students at the top of the scale could speak with confidence and a high degree of accuracy on a wide range of complex matters and could express themselves effectively in most informal and formal writing on practical, social, and professional topics treated both abstractly and concretely. For a complete description of the levels see ACTFL Proficiency Guidelines-Speaking, 1999 and ACTFL Proficiency Guidelines-Writing, 2001.

Speaking and writing in a real-life business context about economic topics usually takes place on an abstract level requiring the use of specific vocabulary and the ability to express complex ideas on a wide variety of topics, all hallmarks of the ACTFL Superior level. Since most of the students did not, in fact, function on that level, I had to make adjustments, and design speaking tasks for the face-to-face classes as well as writing tasks for the on-line components that brought the abstract topics down to a level that students functioning below the Superior level could handle. I often designed several tasks on the same topic, some requiring description and narration, others requiring argumentation. An example of a descriptive task could involve giving factual information found on the Internet about a fair or trade show, whereas the argumentation task would consist of a comparison between two similar fairs and an attempt to persuade a business partner to attend one rather than the otherSuch assignments were task-based and required the integration of cross-cultural information.

Examples of Task-Based Assignments

For the first chapter in the textbook dealing with Germany’s infrastructure and location of key industries, I assembled a list of company websites. Students at the lower proficiency levels were asked to select a company and to design a brochure giving information about the company’s history, location, and infrastructure. This was a narrative task that required students to use the new vocabulary and structures introduced in the textbook. Those functioning on a higher linguistic level would get a task involving persuasion and the expression of opinion in the context of a discussion between a company wanting to relocate to a certain city and representatives from the local chamber of commerce promoting it. The topic dealt with geography and infrastructure, but the linguistic task was more complex. Students with similar linguistic proficiencies worked in groups on their respective projects with the teacher functioning as a resource person when questions or problems arose. According to Brandl (2002), such a student-centered approach gives students a larger role in taking charge of their learning and fosters learner independence and autonomy (p. 89).

Figure 2 shows a sample brochure for Lufthansa designed by a group of students functioning at the threshold between Intermediate High and Advanced Low (see ACTFL Proficiency Guidelines-Speaking, 1999 and ACTFL Proficiency Guidelines-Writing, 2001). It was left up to the individual groups to decide whether to work on the project face-to-face or create and edit the brochures virtually. I set up group pages where they could exchange ideas and documents. All on-line work was done asynchronously.

Figure 2. Sample Lufthansa Brochure.|

|

Adjusting Tasks to Students’ Proficiency Levels

How can one involve non-business majors in an on-line discussion of monetary policy and inflation? The basic concepts and vocabulary contained in the textbook reading and listening texts on the CD-ROM accompanying the book were introduced in the face-to-face portion of the class. For their on-line conversation on BlackBoard’s Discussion Board, students were asked to interview older persons who could remember the economic situation after World War II in their country. They had to find out how much their interviewees earned at that time, what they were able to purchase, how much the prices had risen, how much money they could save, and how they judged their general standard of living. This brought an abstract topic to a concrete level. Students had to summarize their findings and report them on the Discussion Board. These reports served as a point of departure for follow-up questions and comments by their classmates. For instance, students reported about a couple who owned a small butcher shop in Florence and had to cope with the competition from the black market, about German families having to share their apartments with refugees, and about the economic situation in Seoul after the Korean War. The postings were read with great interest and sparked a lively follow-up discussion. Not only did students use the core vocabulary introduced in the lesson, but they exchanged interesting cross-cultural information. Figure 3 shows a posting by one of the students.

Figure 3. Student Posting on the Discussion Board

(see English translation in Appendix B).

|

|

Transatlantic Discussions

An on-line environment makes it possible to establish direct links to the target culture, so the chapter on a planned vs. a free market economy was ideally suited for an on-line discussion with contacts in Eastern Germany about life before and after the fall of the Wall and the demise of the German Democratic Republic. This topic provoked an intense exchange between the students and their Eastern German discussion partners. Students commented repeatedly on the information gained during this exchange in classroom discussions throughout the rest of the course. I used some of the student postings for the reading section of the midterm and final examinations. Students expressed a sense of empowerment from finding texts they had produced included in the tests.

Currency and exchange rates constituted another topic for a transatlantic discussion. I arranged a German contact for each student to discuss the recently introduced Euro. Students functioning at the lower levels could ask questions about the new currency’s effect on prices, and about the first purchases they made with the new currency. More proficient students discussed the impact of the new currency on companies and the economy in general. All students reported their findings to the class and answered follow-up questions.

Further discussion topics were related to management and business administration, such as cross-cultural differences in management styles, global marketing and advertising. Students engaged in an on-line discussion with executives working for German and Swiss multinational companies. They could check whether the general information in the textbook reflected actual business practices or consisted of national stereotypes, such as the Germans’ adherence to schedules and plans, or the Americans’ greater acceptance of risks and professional mobility. The question-answer format gave all students, regardless of their linguistic proficiency, a chance to engage in the discussion and to gain insights into management practices in global companies. This information served as the basis for the next group project - to design a brochure welcoming new German co-workers to a recently opened American subsidiary. According to Brandl (2003), “project work leads to the authentic integration of skills and processing of information from varied sources, mirroring real-life tasks” (p. 93). This was certainly evident in the projects. Students not only paid attention to content and language, but also to the visual presentation of the final product. They proudly handed out their glossy brochures in class.

The final project integrating all aspects of the course was to create an advertising campaign for an American product marketed abroad or a foreign product sold in the U.S. The advertising campaigns reflected the cultural diversity of the students. For instance, student projects introduced Czech housewives to resealable plastic bags, American college students to microwaveable Indian dishes instead of the standard pizza fare, Ukrainian merchants at local markets to backpacks with wheels, Germans to portable energy-efficient air conditioners, and health-conscious Americans to the wonders of Okinawan seaweed.

Outcomes

During the entire course sequence, learning was seen as a process to which students actively contributed. The hybrid format encouraged their lively participation in task-based activities. On-line projects resulted in follow-up class discussions or vice-versa. Whereas in the traditional version of the course the student’s role was more passive, consisting primarily of working with vocabulary building, grammar, and textbook-based listening exercises, the on-line component consisted of postings, with the result that students did considerably more writing in the target language than in a traditional face-to-face course. The initial writing assessment given at the beginning of the course provided baseline data, and, in my opinion, showed a measurable increase in the students’ writing proficiency observed in their projects, postings and particularly in the writing part of the final examination since the questions on the assessment and on the final exam were similar. New vocabulary and structures were more readily integrated into their papers and postings and were better retained. Learners were also exposed to more reading since they had to read each other’s postings, as well as those by the German contacts who participated in the transatlantic exchanges, or the German employees of multinational companies in the New York City area. On-line discussions with native speakers added to the students’ understanding of cross-cultural differences in value-based decisions and management styles. Updating materials in the textbook with the newest on-line information helped to keep the topics current.

PART II: SURVEYS

Student Reactions to the Hybrid Learning Environment

In order to assess student reactions to the newly created hybrid course, a 45-item questionnaire was administered at mid-point and at the end of each semester. The questionnaire consisted of three parts and covered a wide range of topics related to the course. Students answered the questions, using a 5-point scale by checking “strongly disagree,” “disagree,” “slightly agree,” “agree,” or “strongly agree.”

I have selected 10 questions from the survey for a detailed discussion. They shed light on crucial issues regarding hybrid courses. Even though the sample size is small, the results are informative.

Web Interface

Questions 1-3 deal with student reactions to the web interface used in the

course.

Table 2. Q1: Were the F2F and on-line components well-balanced and integrated?

| Strongly agree |

Agree |

Slightly agree |

Disagree |

Strongly disagree |

N |

|

| G 312 mid Fall 2001 |

2 |

6 |

5 |

1 |

0 |

14 |

| G312 end Fall 2001 |

4 |

7 |

3 |

0 |

0 |

14 |

| G313 mid Spring 2002 |

3 |

3 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

6 |

| G313 end Spring 2002 |

3 |

4 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

7 |

| G312 mid Fall 2003 |

2 |

7 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

11 |

| G312 end Fall 2003 |

6 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

8 |

| G313 mid Spring 2004 |

4 |

5 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

10 |

| G313 end Spring 2004 |

3 |

6 |

3 |

0 |

0 |

12 |

Replies to question 1 show general satisfaction with the integration

of the two components of the class.

Table 3. Q2: Was the overall on-line classroom environment conducive to learning?

| Strongly agree |

Agree |

Slightly agree |

Disagree |

Strongly disagree |

N |

|

| G 312 mid Fall 2001 |

5 |

2 |

3 |

1 |

3 |

14 |

| G312 end Fall 2001 |

3 |

5 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

14 |

| G313 mid Spring 2002 |

4 |

2 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

6 |

| G313 end Spring 2002 |

5 |

4 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

9 |

| G312 mid Fall 2003 |

5 |

5 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

11 |

| G312 end Fall 2003 |

6 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

8 |

| G313 mid Spring 2004 |

5 |

5 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

10 |

| G313 end Spring 2004 |

6 |

4 |

2 |

0 |

0 |

12 |

Results show that students felt that the on-line classroom environment was

conducive to learning, except for the respondents in the Fall 2001 mid- and

end-of-semester surveys in which 8 respondents voiced dissatisfaction.

Table 4. Q3: The on-line learning environment as a whole is easy to use.

| Strongly agree |

Agree |

Slightly agree |

Disagree |

Strongly disagree |

N |

|

| G 312 mid Fall 2001 |

1 |

6 |

3 |

2 |

1 |

13 |

| G312 end Fall 2001 |

3 |

6 |

3 |

1 |

2 |

15 |

| G313 mid Spring 2002 |

3 |

4 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

7 |

| G313 end Spring 2002 |

5 |

3 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

8 |

| G312 mid Fall 2003 |

6 |

4 |

2 |

0 |

0 |

12 |

| G312 end Fall 2003 |

5 |

3 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

8 |

| G313 mid Spring 2004 |

4 |

6 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

10 |

| G313 end Spring 2004 |

5 |

6 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

12 |

The highest satisfaction rate was again recorded in Spring 2002 and the lowest in Fall 2001. There are a number of probable explanations for the survey results. None of the students enrolled in the Fall 2001 semester had any previous experience with on-line learning or any previous exposure to the BlackBoard environment. In addition, unforeseeable events affected all of us. After the tragic events of 9/11, some students experienced technical difficulties with their on-line connections. Few students had high-speed internet connections at home, and upgrades in the computer infrastructure on campus had not yet taken place. In addition, it was also the first attempt by the instructor at teaching a hybrid course. As the statistics clearly show, satisfaction rates shot up in the second semester and stayed high thereafter. This may have been due to a number of factors. As Figure 1 above illustrates, I changed the organization of the web page eliminating many navigation steps. I also streamlined due dates and made some assignments optional.

Student Attitudes Toward Working On-line

Questions 4 and 5 dealt with student attitudes towards working on-line.

Table 5. Q4: I felt uncomfortable posting questions in the discussion forum.

| Strongly agree |

Agree |

Slightly agree |

Disagree |

Strongly disagree |

N |

|

| G 312 mid Fall 2001 |

1 |

3 |

4 |

4 |

2 |

14 |

| G312 end Fall 2001 |

2 |

2 |

4 |

3 |

3 |

14 |

| G313 mid Spring 2002 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

3 |

1 |

6 |

| G313 end Spring 2002 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

5 |

7 |

| G312 mid Fall 2003 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

3 |

5 |

11 |

| G312 end Fall 2003 |

1 |

3 |

0 |

1 |

3 |

8 |

| G313 mid Spring 2004 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

4 |

4 |

10 |

| G313 end Spring 2004 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

2 |

7 |

11 |

There were students in all courses who felt uncomfortable posting questions in the discussion forum, e.g., 8 out of 14 respondents in the Fall 2001 semester agreed with the statement in question 4. In Spring 2002, students were most at ease working in an on-line environment and only 1 respondent agreed with the question. These insights into students’ attitudes are of interest to foreign language teachers and also have a bearing on the treatment of error correction. Strambi and Bouvet (2003) state that “[...] Computer Mediated Communication (CMC) seems to provide a non-threatening environment for learners’ experimentation with the target language. In electronic discussions, learners can decide when to contribute, and can prepare their text without pressure or fear of being interrupted. The risk of making mistakes in front of other students and the consequent allocation of cognitive resources to the monitoring of one’s linguistic accuracy and pronunciation also seem to be overcome by CMC” (p. 87).

Other research supports their findings (Blake, 1998; Ware, 2005). I agree with their conclusions that learners can prepare their texts and do not feel pressure to reply instantly as is the case in a regular class. Pronunciation is also no issue. However, an oral utterance in class has no permanence and a mistake may be heard but will be soon forgotten. Certainly, learners can focus more on accuracy when composing a posting, but they know that their postings will always contain mistakes and they continue to be uneasy about showing their work publicly to the entire class. This is supported by the responses to Question 4.

I approached the problem of error correction in two different ways. There was a forum on the website entitled “Grammar Clinic” where the focus was on form. Errors found repeatedly in a number of postings were discussed and numerous examples of correct usage were provided. Individual corrections and comments were e-mailed to the students directly, retaining the same kind of confidentiality as exists in a conventional class. This obviated one of the known sources of learner dissatisfaction in distance learning environments, namely the lack of timely feedback from the instructor (Doughty & Long, 2003; Hara & Kling, 1999).

Table 6. Q5: I get easily distracted in an on-line environment.

| Strongly agree |

Agree |

Slightly agree |

Disagree |

Strongly disagree |

N |

|

| G 312 mid Fall 2001 |

3 |

3 |

1 |

6 |

1 |

14 |

| G312 end Fall 2001 |

3 |

1 |

2 |

4 |

4 |

14 |

| G313 mid Spring 2002 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

3 |

2 |

6 |

| G313 end Spring 2002 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

6 |

7 |

| G312 mid Fall 2003 |

0 |

1 |

3 |

4 |

3 |

11 |

| G312 end Fall 2003 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

5 |

2 |

8 |

| G313 mid Spring 2004 |

1 |

2 |

1 |

3 |

3 |

10 |

| G313 end Spring 2004 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

4 |

6 |

12 |

Students working on the on-line component do so in a solitary environment under unequal conditions such as location, equipment, and distractions, whereas in the traditional classroom setting the conditions are the same for all the learners. In addition, there is also a psychological dimension since not only the teacher but also the peers are missing, and instant feedback and reactions are not possible (Stelzer & Vogelzangs, 1994). As Table 6 clearly shows, the highest number of students reporting distraction as a factor was in the Fall of 2001. These numbers were always higher in the mid-semester survey than at the end of the semester, because with increased exposure to and familiarity with the on-line environment the distraction factor appeared to decrease. Other possible factors that helped students to better focus on the task at hand were streamlining the course website after the first semester, providing very precise instructions, and pre-selecting links to be consulted.

Time Investment

Answers to questions relating to time investment are presented in Tables 7-9 below. Three-credit courses at Hunter College meet for 150 minutes a week on either a two-class or a three-class schedule. The courses described in this article met for 75 minutes on campus and for the “equivalent” time on-line. For this reason, the unit of measurement in Question 8 is 75 minutes.

Table 7. Q6: How often do you access the course website?

| Never |

Occasionally |

Once a week |

Twice a week |

> twice a week |

N |

|

| G 312 mid Fall 2001 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

2 |

9 |

12 |

| G312 end Fall 2001 |

0 |

0 |

4 |

4 |

8 |

16 |

| G313 mid Spring 2002 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

6 |

6 |

| G313 end Spring 2002 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

2 |

6 |

8 |

| G312 mid Fall 2003 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

2 |

9 |

11 |

| G312 end Fall 2003 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

7 |

8 |

| G313 mid Spring 2004 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

8 |

9 |

| G313 end Spring 2004 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

11 |

11 |

Since most on-line assignments had a deadline for the primary task and a second deadline for the follow-up questions, students were expected to access the website twice a week. The responses in Table 7 confirm this, except for the Fall 2001 and the Spring 2004 semesters where 5 students reported accessing the website only once a week. Since I usually posted a summary and comments in the “Grammar Clinic” forum at the end of the week, most of them logged on more than twice a week.

Table 8. Q7: How much time did you spend on the average preparing for the F2F class?

| <1 hour |

1 hour |

2 hours |

3 hours |

>3 hours |

N |

|

| G 312 mid Fall 2001 |

0 |

1 |

5 |

4 |

2 |

12 |

| G312 end Fall 2001 |

0 |

5 |

5 |

2 |

4 |

16 |

| G313 mid Spring 2002 |

0 |

1 |

2 |

1 |

2 |

6 |

| G313 end Spring 2002 |

0 |

1 |

3 |

2 |

2 |

8 |

| G312 mid Fall 2003 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

2 |

0 |

11 |

| G312 end Fall 2003 |

1 |

1 |

5 |

0 |

1 |

8 |

| G313 mid Spring 2004 |

1 |

2 |

2 |

4 |

0 |

9 |

| G313 end Spring 2004 |

1 |

3 |

4 |

3 |

0 |

11 |

| Total |

5 |

17 |

30 |

18 |

11 |

Table 9: Q8: How much time a week do you spend on the on-line assignments?

| <75 mins |

75 mins |

2 hours |

3 hours |

>3 hours |

N |

|

| G 312 mid Fall 2001 |

1 |

1 |

6 |

3 |

1 |

12 |

| G312 end Fall 2001 |

3 |

2 |

4 |

1 |

6 |

16 |

| G313 mid Spring 2002 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

4 |

2 |

6 |

| G313 end Spring 2002 |

0 |

2 |

1 |

2 |

3 |

8 |

| G312 mid Fall 2003 |

3 |

2 |

3 |

3 |

0 |

11 |

| G312 end Fall 2003 |

0 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

8 |

| G313 mid Spring 2004 |

0 |

3 |

3 |

1 |

2 |

9 |

| G313 end Spring 2004 |

0 |

3 |

4 |

1 |

3 |

11 |

| Total |

7 |

15 |

23 |

17 |

19 |

Tables 8 and 9 show that students spent a considerable amount of time on coursework, confirming that learners have to be self-motivated and diligent to be successful in on-line or hybrid courses. Looking at the total number of responses in all four semesters, the median preparation time for the two components was two hours.

In the Fall 2001 surveys, students voiced complaints about the amount of work, particularly for the on-line component. Since there was no need to commute and be physically present in class, the actual time investment for the on-line, compared to the face-to-face class, was less. Since the times are self-reported, it cannot be ascertained whether other factors, such as technical difficulties, general frustration, or the unfamiliar teaching mode led the students to believe that the on-line component was more time-consuming. As a response to the suggestions in the 2001-2002 survey, I adjusted the work load in the 2003-2004 course sequence. For instance, I made some assignments such as work with the CD-ROM voluntary. In the planning phase, I tried to gauge the time investment for the writing assignments but I underestimated the time students spent reading other students’ postings. Ware (2005) also reports that reading and interpreting partners’ messages were a source of tension for her subjects.

Student Satisfaction

Questions 9 and 10 dealt with student satisfaction with regard to effort and accomplishment.

Table 10. Q9: The amount of material covered was adequate for the credit received.

| Strongly agree |

Agree |

Slightly agree |

Disagree |

Strongly disagree |

N |

|

| G 312 mid Fall 2001 |

3 |

6 |

2 |

1 |

2 |

14 |

| G312 end Fall 2001 |

8 |

3 |

3 |

0 |

0 |

14 |

| G313 mid Spring 2002 |

4 |

2 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

6 |

| G313 end Spring 2002 |

4 |

2 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

7 |

| G312 mid Fall 2003 |

3 |

7 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

11 |

| G312 end Fall 2003 |

4 |

4 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

8 |

| G313 mid Spring 2004 |

2 |

6 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

10 |

| G313 end Spring 2004 |

6 |

4 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

12 |

Even though the courses required a major time investment, students generally felt that the credit received was commensurate with the material covered.

Table 11. Q10: I have a sense of accomplishment so far.

| Strongly agree |

Agree |

Slightly agree |

Disagree |

Strongly disagree |

N |

|

| G 312 mid Fall 2001 |

2 |

2 |

5 |

3 |

2 |

14 |

| G312 end Fall 2001 |

7 |

2 |

4 |

1 |

0 |

14 |

| G313 mid Spring 2002 |

4 |

2 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

6 |

| G313 end Spring 2002 |

4 |

3 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

7 |

| G312 mid Fall 2003 |

4 |

5 |

2 |

0 |

0 |

11 |

| G312 end Fall 2003 |

6 |

2 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

8 |

| G313 mid Spring 2004 |

3 |

7 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

10 |

| G313 end Spring 2004 |

8 |

3 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

12 |

The ultimate question is whether the students had a sense of accomplishment at the mid- and end-point of the course. Table 11 shows that learners, in general, did report such feelings. The largest number of negative responses occurred in the Fall 2001 mid-semester survey. In all subsequent surveys responses were all in the positive range.

Responses to the ten questions above showed an overall consensus on the part of the students that the course objectives had been met. However, individual categories showed fluctuations between the middle and end of the semester, as well as between individual courses. The course with the most positive feedback was German 313, Spring 2002. This can be attributed to a number of factors. It was the smallest, most homogeneous class with only 9 students. Based on the writing assessment given at the beginning of the term, all students functioned at about the same level, and most of them had been enrolled in the previous semester and thus had experience with the on-line learning environment. They also spent slightly more time preparing for the face-to-face class (median 2.5 hours) and on the on-line class (median 3 hours). In addition, changes made by the instructor with regard to the interface and workload may have also contributed to a higher rate of satisfaction.

CONCLUSIONS

A number of conclusions can be made based on the 2-semester hybrid course described in this article. First, as mentioned above, learners have to be self-motivated in order to succeed in this type of learning environment. Second, for this particular set of courses, students should have advanced proficiency in the language since many tasks are of narrative nature. Participating in on-line discussions, especially those with native speakers of German who are not used to dealing with language learners, can prove to be too difficult and frustrating for learners at lower levels of proficiency. Nevertheless these transatlantic exchanges were among the most informative aspects of the course. Third, this type of course requires a considerable time investment on the part of the learners. Students are not alone in having to invest a lot of time in such a course. So does the teacher since new pedagogies and different approaches must be developed assuring the seamless integration of the face-to-face and on-line components. Furthermore, good surveys are needed to get feedback from the students. The insights I gained from them helped to make the necessary adjustments that resulted in greater student satisfaction and learning. The combination of traditional classroom work with a focus on speaking and the task- and proficiency-based writing activities in the on-line component seems to be an ideal setup to foster overall language development.

NOTES

[1]The

author would like to thank Hunter College, CUNY, for a faculty development

grant sponsored by the Alfred E. Sloan Foundation, as well as the National

Foreign Language Resource Center at the University of Hawai‘i at Manoa for

their support of this project. Preliminary findings were presented at the

MLA Annual Convention, December 27, 2002.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Annette Kym, PhD, is Associate Professor and Chair of the German Department at Hunter College, CUNY, where she teaches language and literature courses at all levels. Among her special interests are proficiency-based language teaching and testing, language for special purposes, and foreign language distance education and distributed learning.

E-mail: akym@hunter.cuny.edu

REFERENCES

American Council on the Teaching of Foreign Languages. (1999). ACTFL Proficiency Guidelines—Speaking. Hastings-on-Hudson, NY: Author. Retrieved on September 16, 2005 from http://www.actfl.org/files/public/Guidelinesspeak.pdf.

American Council on the Teaching of Foreign Languages. (2001). ACTFL Preliminary Proficiency Guidelines—Writing. Hastings-on-Hudson, NY: Author. Retrieved on September 16, 2005 from http://www.actfl.org/files/public/writingguidelines.pdf.

Brandl, K. (2002). Integrating Internet-based reading materials into the foreign language curriculum: From teacher- to student-centered approaches. Language Learning & Technology, 6(3), 87-107. Retrieved October 15, 2004 from http://llt.msu.edu/vol6num3/brandl/default.html.

Blake, R. J. (1998). The role of technology in second language learning. In H. Byrnes (ed.), Learning foreign and second languages (pp. 208-237). New York: Modern Language Association.

Doughty, C. & Long, M. (2003). Optimal psycholinguistic environments for distance foreign language learning. Language Learning & Technology, 7(3). Retrieved October 31, 2004 from http://llt.msu.edu/vol7num3/doughty/default.html.

Hara N., & Kling R. (1999). Students’ frustrations with a web-based distance education course. First Monday, 4(12). Retrieved October 15, 2004 from http://www.firstmonday.org/issues/issue4_12/hara/index.html.

Omaggio Hadley, A. (1993). Teaching language in context (2nd ed.). Boston: Heinle & Heinle.

Paulsell, P.,Gramberg, A., & Evans K. (2000). German for business and economics, (Vols. I & II), (2nd ed.). East Lansing, MI: Michigan State University Press.

Stelzer, M. & Vogelzangs, I. (1994). Isolation and motivation in on-line and distance learning courses. In On-line and distance education (Chapter 8). Retrieved December 5, 2004 from http://projects.edte.utwente.nl/ism/Online95/Campus/library/online94/chap8/chap8.htm.

Strambi, A. & Bouvet, E. (2003). Flexibility and interaction at a distance: A mixed-mode environment for language learning. Language Learning & Technology, 7(3). Retrieved October 15, 2004 from http://llt.msu.edu/vol7num3/strambi/default.html.

Thompson, M. (2004). Faculty self-study research project: Examining the online workload. Journal of Asynchronous Learning Networks, 8(3). Retrieved June 7, 2005 from http://www.sloan-c.org/publications/jaln/v8n3/index.asp.

Ware, P. (2005). “Missed” communication in on-line communication: Tensions in a German-American telecollaboration. Language Learning & Technology, 9(2), 64-89. Retrieved June 17, 2005 from http://llt.msu.edu/vol9num2/ware/default.html.

Zemsky R., & Massy W. F. (2004, July 9). Why the e-learning boom went bust. The Chronicle of Higher Education, pp. B6-B8.

APPENDIX A

GERMAN 313.51 ADVANCED BUSINESS GERMAN SPRING 2004

Writing Assessment Name:_________________________

Exercise (in-class)

THIS IS NOT A TEST. It is only an exercise which will help me suggest to you how you should proceed with your work on writing in this course.

Please answer the questions below in the sequence they are listed. Do not worry if you cannot answer all the questions or if you run out of time.

1. You are working for a company. Write yourself a short note, listing the tasks you have to do today.

2. This company is selling a product or a service. Describe it in general terms. (Include information such as country of origin, quality, price, other details such as fabric content, ingredients, etc.)

3. Your company wants to expand to other markets (with maybe a new product). Suggest the steps it would take to do this. What advantages would this bring for your company and for the potential client/user of the product? Write a paragraph in which you state and support your arguments for this plan and hypothesize about its outcome.

APPENDIX B

Translation of student posting

When World War II ended, my grandmother was twenty-five years old. She lived in Florence, Italy, and she was already married. She did not work, but her husband owned a butcher shop in the vicinity of Florence.

She remembers that people were very happy at the end of the war; nevertheless, the economic situation in the city was terrible because of the high unemployment, lack of food and high consumer prices. In general, family incomes and wages dropped, whereas the cost of living rose.

The profits of my grandfather’s store diminished, nobody could afford meat since prices climbed. Furthermore, one could buy meat as well as other low-priced goods, such as cigarettes or soap on the black market. Therefore, his business lost many customers. For these reasons, my grandmother had little money to buy food and satisfy other needs. But she said that they were very happy, because her father and her mother had planted a vegetable garden. Thus, my grandmother received often vegetables or eggs from her family. Not only tea and coffee but chocolate and sugar were also unavailable. She said that she did not drink any coffee or eat any chocolate for 6 years. Furthermore, medicine was in short supply and difficult to find. It was expensive, therefore she prepared natural remedies made from onions, garlic or other herbs at home. Slowly, the economy improved, but my grandmother could save little money because the average income was still low. Everything she earned she had to spend. She could not afford any extras, such as travel or clothes. Sometimes she went with her husband to the movies shown in the church, only because they were free of charge.

Contact: Editors

Copyright © 2005 National Foreign Language Resource Center

Articles are copyrighted by their respective authors.