Culture differs not only across national boundaries, but across communities and social classes within those boundaries, and even across generations within the same group. As history recedes, the cultural values prevalent in earlier generations become less accessible to young people. Teenagers may wonder why their parents, for example, find an older movie so funny or so fascinating. The answer, of course, is that their parents relate to the movie because of a personal connection with the movie established when they were younger. Once a younger person can successfully establish a personal connection to historical material, they will engage with it in their own way.

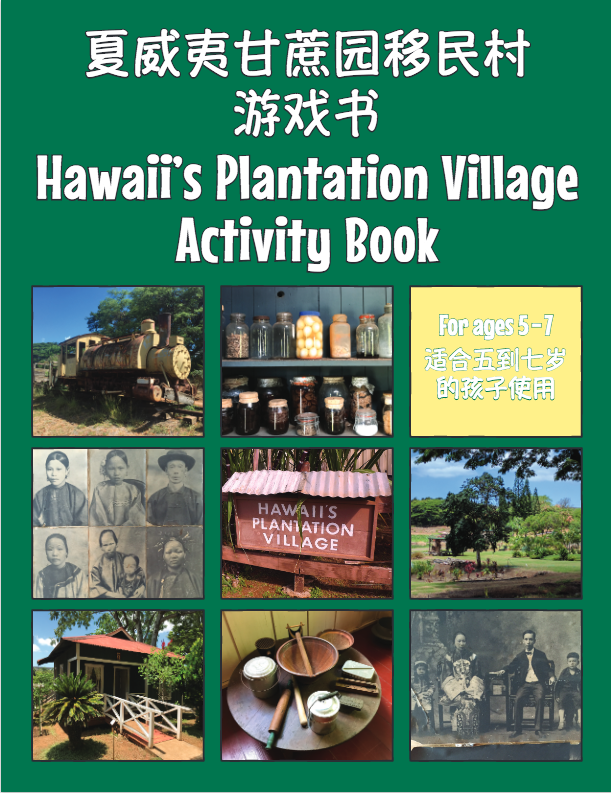

With this in mind, this Chinese-language project for beginning learners is aimed at creating a product to help younger visitors (ages 5~7) to a particular historic spot on the island of O‘ahu to make connections between what they see in displays of historical material and their own lives, even if they do not speak English, the language in which most of the museum's tours and displays are offered. What is special about this project in the context of PBLL (Project-Based Language Learning) is that the project is designed for learners at the Novice Low, or zero-beginner, level. It is conceived as a model for Day 1 of a project-based (or partially project-based) language learning curriculum. As such, it represents a challenge to the notion that beginning learners, with their extremely limited functional communicative capacity in the target language, cannot engage in language use connected with deeper inquiry into a challenging problem or question for authentic purposes with an impact on a public audience.

In PBL (Project-Based Learning) in general, curricular design is specific to the time, place, and community in which it is conducted. While a PBL project design may have rich referential value for other designers, it will never be exportable as is, because it is (ideally!) always created to fit a challenging problem or question, to which the learners respond with a project product directed at a specified public audience. In addition, since "there is no perfect PBL," the reader will no doubt see aspects in the design of the project that they might handle differently. With these caveats, the project design is offered for free adaptation, and I look forward to seeing derivations of this project in the future.

Typically, learners in beginning language courses are not asked to consider or explore cultural problems or questions in depth. This project is an attempt to harness the generational/historical cultural disconnect described above as a driving force in the creation of a product for children: an activity book connected with a particular cultural attraction, the Hawaii's Plantation Village outdoor museum. This activity book is designed to facilitate the creation of connections in the children's minds between the dusty artifacts and aged houses visible in the Village and their own lived experience. The imperative that learners in this project should design activities to foster such connections puts this project on a different level than most tasks for beginning learners -- in essence, bringing cultural and cognitive challenges into the picture that are not typically expected in beginning language materials, and situating the learners as investigators (obtaining language they need) and creative thinkers (designing activities).

This project was designed "in miniature" -- in other words, designed for a short timeframe with limited objectives -- and should perhaps be further expanded and elaborated if it is adopted as part of an academic curriculum. In the two-day timeframe of the project, a group of beginning learners of Mandarin Chinese, accompanied by several "language experts" -- speakers of Chinese who had agreed to work in support of the project -- followed the following major steps:

Returning to the question of PBLL at the Novice level, I think that this project suggests not only that deeper inquiry is possible for beginning learners, but also that educators pursuing PBLL may find that their target construct -- in other words, the set of skills and knowledge from which they derive instructional objectives -- requires radical readjustment. Most instruction for absolute beginners in Mandarin Chinese focuses on associating sounds and symbols for the Pinyin romanization system, perhaps learning a few foundational characters, and memorizing some expressions related to meeting others for the first time (greetings, name, nationality, thanks, leavetaking). The goal of such a program of instruction might be expressed as "to acquire enough communicative capacity in Chinese to be able to function well in China someday." The target construct is large and distant; learners are beginning a long, slow climb toward "being a proficient communicator." Meanwhile, learners' real-world agency in this paradigm is close to zero; they are, essentially, role-playing a future, proficient self.

PBLL, in contrast, begins with work on a challenging problem or question (the "Driving Question"), and work on "learning language" is mixed in with all the other pieces that are needed to address the Driving Question. This particular project begins with a comprehensible story about a little girl named Jiajia. The story is unrelated to any social use of language: it's not about meeting people someday in China. The purpose of the story is to orient the learner toward a challenging real-world problem: Chinese-speaking kids probably can't relate very well to what they see at a certain museum. In the Jiajia story, the most salient language pieces (for example, the iron her mother uses, or the verb "sees," which is used repeatedly) are not immediately useful as fodder for interpersonal communication; there is no immediate communicative goal connected with Jiajia. But in contrast to the traditional curriculum, the story forms part of a program of instruction whose aim is to address a challenging problem or question which is both comparatively limited in scope and immediately present, providing a challenge with clear value and a visible endpoint. Learners' use of language in the project is not a rehearsal for some future moment; there are no model dialogues, and they are never asked to play a role other than themselves.

When the moment for learners to use Chinese to achieve a purpose does arrive in this project, that use is totally scaffolded by a prepared script, and the only criterion for accurate production by these beginning learners is whether they get the items they request from the language expert. So in a sense, in this particular project, learners are never asked to role-play a future, proficient self. While instruction is geared toward the learners' status as Novice Low speakers, there is no imperative to begin with greetings, or shopping, or numbers. It is assumed that, given sufficient project work, learners will develop proficiency; however, their pathway to proficiency is governed by the "need-to-knows" of the project at hand, not by putative future life tasks. This being the case, it is obvious that procedural language of the kind needed to work collaboratively, to gather and test information, to query cultural values, and even (depending on the project product) to construct material objects or stage a drama will figure much more prominently in PBLL curricula, while travel scenarios, chats about the weather, and restaurant orders will figure less. Another corollary: given that even beginning-level projects in PBLL are expected to feature deeper inquiry -- to engage learners with questions that have no established answers -- scaffolding takes on new significance. The teacher mindset of being loath to "give answers away" fades into insignificance, as the teacher is no longer the sole arbiter of "the answer." In a non-PBLL paradigm, a teacher might object on principle to learners' use of helps such as a "cheat sheet" of useful expressions or a software translator, because such learners would be breaking the fourth wall in the theatre of their future, proficient self. In PBLL, a teacher's view would likely be that a learner should be free to use such helps as necessary, in pursuit of the larger "answer," of which she cannot possibly be a gatekeeper, since it is only arrived at through conduct of the project. A teacher might, on the other hand, be very concerned about a student's ability to work collaboratively toward a common goal.

One of the biggest challenges in using the ideas of Project-Based Learning for language instruction is that beginning learners have almost no functional communicative capacity, and yet PBL demands that they extend their learning beyond the walls of the classroom to create some kind of real-world impact. I believe this design supports the notion that even beginning learners can meet this challenge, and that significant connections with communities can be included from the very beginning of a language learner's journey. --Stephen Tschudi

Project idea development and connecting with project partner

Input activity / Entry Event

Examine existing exemplars

Tour Hawaii's Plantation Village

Determine "need-to-knows" for the project

Sketch out activity design

Prepare to use the target language

Interview language informants

Draft activity design in TL in group document online

Post-production and publication

Ongoing assessment and evaluation

Implementation information not specified.

Hawaii's Plantation Village, an outdoor museum highlighting Hawaii's plantation labor heritage, is run by a community-based nonprofit and operates on a minimal budget. In recent years the Village has acquired a modicum of fame locally as the location of one of the top-ten scariest Halloween attractions nationwide, the Haunted Plantation, which was featured on the television show "Ghost Hunters," but most of the time the museum is open in the daytime, offering docent-led tours of the museum's "village" of plantation-style worker housing, offices, shops, temples, and social spaces. Many of the docents are descendants of immigrant sugarcane workers and have connections to the local Waipahu sugar mill (now converted into a community center). As such, they have rich and varied knowledge of the various ethnic groups that made up Hawaii's plantation labor culture and of how plantation life used to be, so each tour is likely to yield new historical treasure for the visitor. Given that Hawaii's sugar-producing days are over and the economy has shifted away from agriculture, HPV has particular significance as a locus for historical preservation.

However, due to the Village's budgetary limitations, it is not really well-resourced enough to reach its full potential in terms of curating of its trove of artifacts, developing interpretive displays, editing and printing visitor guides, and so forth. Many of the existing displays are showing their age or have an improvised air, and while HPV does host scores of school group visits each year that feature activities such as trying on ethnic garb or learning how to perform lion dances, non school-group visitors of school age are not provided with anything beyond a basic schematic of the layout of the Village's structures. With this in mind, developing a resource in support of the visitor experience for children became the starting point for this project.

The idea of creating an activity book focusing on forming associative connections between a child's own life experience and the things he or she would see at HPV was arrived at only after a long gestational period. Given that the targeted level of instruction was Novice, the idea of a product for children was settled upon fairly quickly. But the shape and theme of the product took a long time to emerge. There were detours into exploring the different jobs that plantation workers used to do, creating a coloring book or a story book, or even designing a scavenger hunt. The idea to produce an age-appropriate activity book of the type that parents use to keep the kids quiet on a long road trip was arrived at only after we had been in contact with HPV staff for quite a while -- assuring them that we would come up with SOME idea -- and a fairly short time before the actual beginning of the project.

Since we were in contact with HPV staff (acually with the Executive Director) for many months in advance of the project, and made some preliminary visits to the Village to discuss the possibilities for collaboration, we were well known to them, and making arrangements for the group visit was a relatively simple matter aside from the usual logistic complexities -- scheduling, transportation, and food. HPV kindly granted us the use of an air-conditioned activity room to use on the day of the project visit after we finished our tour.

We knew that we would want to use actual images of Village buildings and artifacts as the basis for activities in the activity book, but we anticipated that it might be frustrating to attempt to gather images from the learners' individual devices in real time on the day of the visit. Therefore, we did an advance visit with the specific aim of taking lots of pictures, after which we placed more than 200 photos we had taken into an accessible folder in Google Drive, so that the learners could simply choose and use images. (Of course, we did not restrict them from using their own images if they wanted to.)

After creating the image archive, we took the additional step of trying our own hand at activity design, producing several prototypes that could serve as examples for the learners. Additionally, we examined a good number of existing commercially produced activity books and from them distilled 16 common activity types for which we created generic instructions in English, accompanied by translations in Chinese and Pinyin romanization, for the reference of the learners. In addition to these resources, of course we had to create the other "pieces" you will see in the subsequent stages of the project. It is perhaps worth noting that the comprehensible-input story used in the Entry Event was conceived and composed just two days before it was used in the project, replacing an earlier Entry Event document that presented the project idea in English. The story turned out to be a key element in the project, providing a beautiful, level-appropriate entrée into Mandarin Chinese while effectively embodying the Driving Question in the story of a little girl who visits Hawaii's Plantation Village and succeeds in making a connection between an unfamiliar object she sees there and a familiar object she has seen her mother use.

Variations of this project (non-English resource for young visitors) can be imagined for practically any museum.

Google Drive provided an effective repository for project planning documents.

Establishing a working relationship with the institution in advance is obviously essential.

This story about a little girl is intended to reify the motivation behind the project, viz., the idea that younger visitors to Hawaii's Plantation Village will benefit from a resource that helps them make connections between what they see at HPV and their own lives. In the story, a 6-year-old girl named Jiajia sees her mother ironing and develops a mental image of the concept "clothes iron." Later, her mother takes her to visit HPV and Jiajia sees an object that she is not able to identify. When she asks her mother, her mother tells her "That's an iron!" and Jiajia suddenly realizes that a clothes iron from the past looks different from a clothes iron today. The story concludes with Jiajia's mother giving her an activity book from HPV in which Jiajia finds a connect-the-dots activity. When Jiajia connects the dots, she sees an iron and she is very happy.

This story was presented onscreen with live narration modified to suit zero-beginners, using lots of repetition, gesture, slowed-down speech, etc. At various points during this first day, such as on the bus going to HPV, the story was repeated without visuals as a means of spaced repetition. Although the story is not really intended as anything more than a framing device, it was plain that some of the language in the story "rubbed off" on the learners, and that they were primed to hear some of the language in the story recycled into other comprehensible input or tasks.

Below is a narrated version of the story produced after the fact as reinforcement for the learners. The slides from the story are also attached as a PDF. (Look for three dots near the bottom of this page and follow the link.)

Following the input story activity, learners were presented with the Driving Question:

In an instructional sequence longer than this project (which is quite limited in scope), one might carry the character of Jiajia forward and base other project products on similar projections of her needs and wants.

Slideshow was produced in Google Slides, which can be exported as a PDF. The narrated movie was produced as a screen capture using QuickTime Player on a Mac, then uploaded and published in YouTube.

It is very important that the story be presented as comprehensible input (though not perhaps 100% comprehensible) with suitable modulations of language.

Following the story input phase, learners were taken by bus to visit Hawaii's Plantation Village. On the half-hour bus trip, they were offered a number of examples of activity books for children and were asked (in English) to discuss with a seat-mate what activities they liked best and why. They were asked to consider attractiveness and clarity of layout, clarity of instructions, pedagogic benefit, and overall appeal, and to start thinking about what kind of activity they themselves might like to design.

Given that these are zero-beginners, we asked them to complete this task in English. It is difficult to imagine how the L2 might be deployed in this instance, unless there were perhaps an L2 form the learners had to fill out to "rate" the workbooks -- in which case they would need a key to decipher the rating form. It doesn't seem worth the investment.

No technology required

A variety of commercially-produced children's activity books had to be procured and used for this activity, which represents an organizational challenge / expense.

The typical visit to HPV involves a guided tour about two hours in duration. Since we felt it was important for the learners to know what their target audience for the final Public Product would experience, we had them go on the typical tour before beginning brainstorming their ideas for the activity they themselves would like to develop for the Activity Book.

In a longer-term project, the capture and curation of images could become a point of focus for further language development and technology skills development. By providing the scaffolding of the image archive, we reduced cognitive and affective load on the learners.

Learners were informed in advance about the image archive in Google Drive, so they were freed from the necessity of capturing and curating their own images.

Organizing the logistics of a group museum visit is always a challenge. We had the expense of bus transportation, lunches and beverages for the participants, and museum admissions.

Inquiry by learners in PBL is driven by what learners need to know in order to successfully produce the Public Product, including all the component steps along the way. If, for example, the Public Product is to be based on data gathered by the learners, then the "need-to-knows" for the project will include not only the needed data itself, but how to gather and assess the data. With this in mind, a PBL designer can project the "need-to-knows" for a given project, but she may not be able to make a final determination on what they are until she gets input from the students, or has even embarked on the project, as some "need-to-knows" may only become apparent as a project proceeds.

In this project, the "need-to-knows" were fairly straightforward; the designer prepared this slide set

and went through it at HPV just after the tour was completed, projecting the slides on the wall, walking through them briefly and asking for any questions. The slide set anticipated questions learners might have and pointed them to resources to help with some of the questions. This way, learners could always return to the slide set and follow the links when needed, strengthening their ability to work independently.

If I rework this slide set in the future, I would like to find ways to build in the target language and use images more effectively to support comprehension.

Google Slides is an ideal medium for developing a "need to know" document.

Learners must have a clear concept of the Public Product for a "need to know" document to be effective. The teacher should anticipate adding to or modifying the document based on student input.

At this point, learners have looked at sample activity books, have taken the tour of Hawaii's Plantation Village, and have been encouraged to think of an activity of their own that will help Chinese-speaking children connect what they see at the Village to their own lives. They have also have seen the example connect-the-dots activity that the little girl in the story (Jiajia) completes to make the connection between the modern iron that she sees her mother use and the rusty old iron she sees at the Village. As part of the Need-to-Knows, the learners have seen the teacher's expectations with regard to their activity design -- that it needs to have a title, an illustration based on a photo from the Village, and a set of instructions.

So at this point the time is ripe for the learners to put their idea on paper, sketching out a title, an image, and a set of instructions, and to give and receive feedback on the activity ideas with their classmates. The teacher shows another example activity and invites the learners to use large-format newsprint and marker pens or crayons to rough out their design. The teacher also specifies that once an activity design is finished, it is to be posted on the wall for a "Gallery Walk" in which other learners will stroll by and annotate the posters with "I like" and "I wonder if" statements to provide feedback. The whole process takes a little over half an hour. In this case, learners tracked their progress on the design task using a checklist.

This process could profit from iteration, i.e., having the learners re-sketch and do a second Gallery Walk to refine activity ideas.

Technology tools could substitute for the large-paper format, but there is something about working on paper that seems to get the creative juices flowing!

Learners who are not accustomed to critique and revision may hesitate to offer feedback suggesting revisions; the "I wonder if" format of the critical comments is designed to mitigate any negativity. It is very important to allow sufficient time in the instructional plan for this activity; in our experience, activity designs underwent significant revision through this process.

In the Need-to-Knows, the learners are offered various resources for the completion of their project. It is assumed that the beginning learner needs total scaffolding in order to accomplish any task that uses Chinese, since the learners have no previous background, and they have had just one story's worth of comprehensible input. For example, the learners do not know the Chinese sound system, and do not know how to pronounce something written in Pinyin, much less characters. To delay use of the language until after learners master Pinyin and the sound system would mean adding a considerable time cost, with the attendant risk of a loss of student drive and motivation. Therefore, rather than conceiving the learner's need in terms of "language they need to learn" to accomplish a task, this project design conceives of need in terms of "rough-and-ready tools they need to use." Granted, this implies that students will be using language without some of the background information that beginning learners typically gain in the first few weeks of instruction, and that their production accuracy will be low. The risk of forming bad habits or making gross errors is considered worth the potential return of successful production of the public product.

Two key tools listed in the Need-to-Knows prepare learners to use the target language to produce their page for the activity book. One is a table of instructions for a set of 16 different activities typically found in children's activity books, such as Connect-the-Dots, Color the Picture, Spot the Difference, etc., all provided in English, Pinyin, and Chinese characters. The other is a flexible script for an interview with a language informant, designed to help the learners obtain language that they wish to use in their activity design. In this case, "obtain language" means to come away from the interview with a paper on which the interviewer has successfully directed the informant to write the desired phrases in Pinyin and in Chinese characters. This paper will be useful to the learners when they do layout of their activity in the group Activity Book draft online.

In line with the "rough and ready tools" concept, the teacher does not engage in extensive practice with the learners using the model activity instructions or the interview script. Instead, the teacher leads the students on a listen-and-repeat of the interview script, and then models one brief interview with one of the informants. Participants are directed to perform the interview in pairs, i.e., two learners interview one informant. The teacher holds up an example and reminds them of their goal for the interview: obtain a paper with the instructions they need for their activity, written in Chinese characters and Pinyin.

In the original project design, participants were expected to perform these interviews by the end of the first day's time at Hawaii's Plantation Village. This proved to be impracticable in the allotted time, so the interviews were carried out on the following day. In this particular instance, five Chinese-speaking informants were available to serve pairs of participants. In a classroom situation in which native-speaking informants are not readily available, the design can be modified so that the teacher is the informant; further variations can be imagined in which students attempt to pose interview questions asynchronously online via audio recording, and the teacher responds to each audio recording in writing -- or, if the teacher wishes to eliminate the learners' need to type, the teacher can respond via email so that the learners can copy and paste text directly from the email.

Having received and reviewed the "cheat sheets," the learners are ready to embark on their "language-getting" interviews.

If there had been more time available, the instructor might have had the learners stage mock interviews using the "cheat sheets," but instead of asking "how do you say X in Chinese" they might have been prompted to ask for different information -- for example, "How is your last name pronounced?" and "How do you spell your last name?" These questions are very similar to those on the "Survival Sheet."

In this case, the teacher distributed paper copies and reviewed the docs using a projector. As mentioned above, other technology-enabled variants on the interview process are possible.

The teacher will need to adjust his or her thinking to get used to the idea that students will be using "cheat sheets" and stabbing wildly at pronunciation to communicate from the very beginning. An approach in which students worked on spelling and sounds before attempting any communicative use of the language would probably not be an appropriate fit for this project-based curricular model.

In the previous step, "Prepare to use the target language," learners have had a short orientation to the process of getting into, through, and out of an interview with a native speaker to obtain a written version (in characters and Pinyin) of the activity title, instructions, and any other language they need to design their activity in the drafting document. In this step, they carry out the actual interview. In this case, the group of learners had access to several native-speaking informants, but in various other instructional contexts, a teacher might have to use alternative strategies to help the learners "source" the language they need.

Depending on the time available, the teacher might want to draw out formulaic language from the interview script and use in in a language practice activity. For example, students might practice an interview with one another in which they become more familiar with getting into, through, and out of a query process by (1) asking whether the other person is free, (2) using the polite preface to a request for information, (3) asking how to spell their names in English, (4) thanking the other person and expressing gratitude for their effort. In this way, the utterances used in the interview would begin their transition from "rough-and-ready tools to use" to "language we are starting to learn and practice."

In this case, the interviews were performed face to face. Technology-based alternatives to this model are possible.

At this point, learners have a critiqued and revised English version of their activity (on poster paper) and have a written version of the Chinese language they need for their activity design. In this task, they process any images they need, then proceed to a group document that has been preformatted as a drafting space for the activity workbook. In this instance, we used Google Slides as a drafting platform, with the slide format set to match a standard publication format The teacher needs to scaffold the activity workbook design by assuming responsibility for parts of the design that are beyond the learners' capabilities, such as drafting the front material (cover, title page, colophon info).

The step begins with a transfer of ideas from paper to pixels: learners need to transfer their activity idea from the marked-up poster paper, plus the target-language instructions (Pinyin and characters) they obtained from their language informant, to an electronic design document. The challenges in this step include (1) working jointly in an electronic design format with which the learner may or may not be familiar, without destroying other people's work; (2) selecting and digitally manipulating an image file to be suitable for the activity-book format; (3) typing in Chinese using the paper-based Pinyin-and-characters "clues" the learner has obtained from the informant.

In this particular instance, although originally planned for the end of the first day, this step was performed the day after the learners had returned from their field trip to Hawaii's Plantation Village. The master Google Slides document was ready with a page for each participant to work in. Some used their own computers and some used lab computers to work on layout. Learners' attention was redirected to the "Need-to-Knows" document, where support for their work was provided with a tutorial on basic skills in Google Slides, search results on how to type Chinese text on the computer, and a link to "Stencil Maker," which allows a user to abstract a photo for use as an illustration. Learners helped one another to complete their layout in Google Slides. In several instances, the language informants provided additional guidance on language when requested by learners.

If the application used is Google Slides, learners will (of course) need to have Google accounts to edit the document.

There are several possible variants of this portion of the project scenario. In a "max PBL" situation, in which learners are taking the maximum amount of responsibility for bringing the project to completion, postproduction would be performed by the learners in duly organized committees. Tasks include the work of finalizing layout (in our case, we used a sophisticated page-layout program), determining the exact publication format (Glossy or matte? Cover design? Designation of copyright?), shopping for printing bids, identifying funding sources, and distributing the printed books. In this particular case, after the teacher had provided the learners with a final round of feedback and learners had made their last revisions, the teacher and university staff performed all of the above-listed steps to bring the product to final publication and distribution. Two hundred copies of the activity book were delivered to Hawaii's Plantation Village for them to offer to young Chinese-speaking visitors. You can view a PDF of the book (file size 10MB).

As a "mini-project" experience, this project design was focused more on having participants experience PBLL from the student perspective than it was on language acquisition per se. As designers, while we were interested in how this project "worked" as an initial language use experience -- and whether learners came away with some bits of language -- we were equally interested in activating participants' awareness of themselves as project team members: how prepared and motivated they felt, and how they liked the project design. All of these aspects of (self-)assessment and evaluation were combined into a journal-style assessment and evaluation worksheet that participants were directed to revisit and complete the appropriate section of after each segment of the project.

While the use of more traditional-style language assessment tools is definitely not excluded as an assessment possibility in PBLL, in this particular context the designers felt it was important to engage the participants in self-assessment -- not to mention that the notion of "mastery" of particular bits of language in such a short beginning experience is not particularly useful.

Comments